Burns service at The Alfred boosted thanks to firefighters donation

A glimpse of an exciting future for patients with complex major burns injuries via bioengineered skin is more advanced than ever before thanks to a burgeoning partnership between the Victorian Adult Burns Service (VABS) at The Alfred and the Firefighters Charity Fund (FCF).

Bioengineered skin – a breakthrough more than 10 years in the making when first used on a patient in 2023 – is the focus of an ongoing trial at VABS, led by reconstructive plastic surgeon at The Alfred, Associate Professor Heather Cleland.

The Alfred is already a world-leader in burns treatment, innovation and development, and projects such as this only further the impact and benefits that patients and staff can experience.

Despite many advances in treatment options, the traditional split skin graft as a main method of closing burn wounds has not changed in more than 150 years.

For those patients needing something better suited to deep burns, this is where engineered skin sheets are starting to show far-reaching effects.

In a first-of-its-kind phase 1 clinical trial, a Melbourne patient had burn wounds repaired using The Alfred bioengineered skin in late 2024, decreasing the need for skin grafting. A major step forward in the treatment of burns, patients' extensive full thickness burns are successfully treated with new skin grown from their own skin cells in a laboratory based at The Alfred.

This trial, a collaboration between The Alfred and Monash University, is funded through the Medical Research Future Fund.

"Almost half of severe burns survivors live with pain and disability caused by scarring and infection, made worse by the need to use traditional skin grafts," A/Prof Cleland said. "With this technique, we are cultivating skin that is practical and safe, thereby eliminating the need for grafting using the patient's unburnt skin for donor sites. This will significantly improve the outcomes for patients with very serious burns."

Currently, it takes four weeks to produce enough skin for one patient while they stabilise in hospital. Thanks to the support of the FCF, the trial can expand, forging new paths in burns care and offering hope to patients with severe burns.

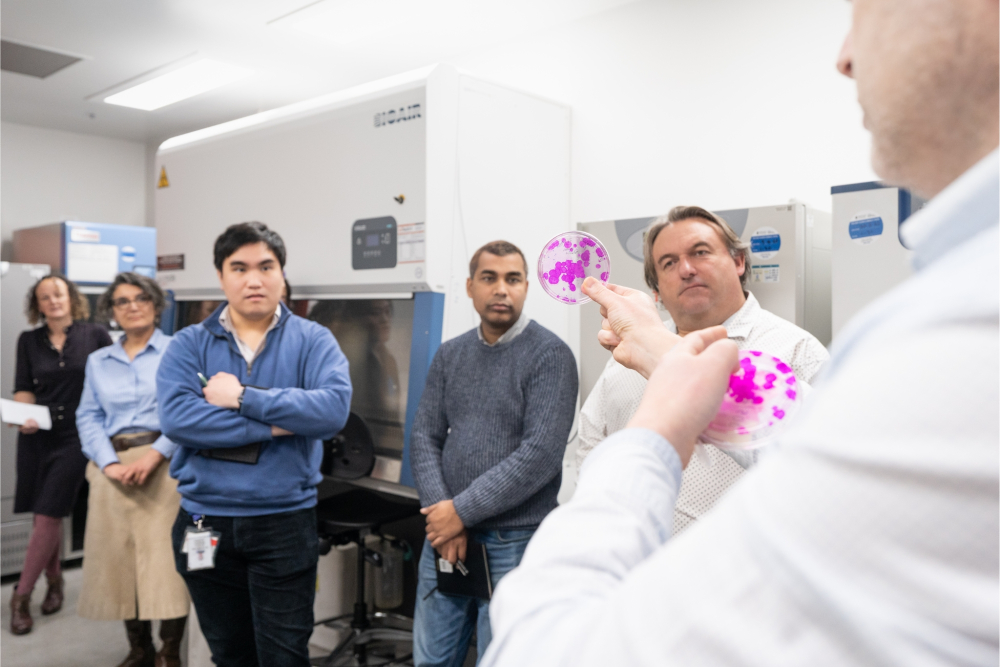

“The donation has allowed us to expand our manufacturing capacities and treat more than one patient at a time, which is huge – because we don’t know when the next patient will come through our door,” Group Leader at the Skin Bioengineering Laboratory, A/Prof Akbarzadeh, said. “We are grateful and honoured to receive this support from the FCF – we feel that they understand the problem and are a big supporter of burns research and treatment.”

Further benefits include a ‘smoother-looking' skin in the months post-grafting, while patients also experience ‘less pulling’ as they recover.

FCF board member Andy Morton said being able to support projects such as this was one of the central tenets to the Fund’s aims.

“About 80 per cent of our firefighters donate weekly, with the four key areas being cancer, children’s health, mental health and burns,” he said. “If everyone gives a little, it adds up to a lot.

“This research is an extension of why we do what we do as firefighters. Our firefighters are invested people who are part of the community and all the money that we raise goes back to the community.

“It is a source of great pride for all our board to show our members ‘look what you’ve done’. It’s amazing that we can see that difference in the community.”

How the bioengineered skin is made

When trial patients with severe, full-thickness burns arrive (burns which have gone through the top two skin layers and into the underlying muscle, bone or fat below), a small sample of their healthy, unburnt skin is taken.

The patients’ own skin cells are isolated and expanded, allowing them to form new skin in sheets in the lab’s incubators.

From skin cell harvest, it takes about four weeks to grow the mature skin. While this is happening, the patients’ burns are covered with another Australian invention, BTM (biodegradable temporising matrix), which acts like the top layer of skin and buys time for the engineered skin to be produced.

The engineered skin is then surgically grafted onto the patient, over the BTM matrix, which eventually breaks down.

This story featured in the Impossible publication of Spring 2025.